Covid-19 and The Police

In 2020, during the Covid-19 lockdown, it became apparent to people who don’t usually observe the police that something bizarre was happening. There were several incidents, all unique in their own way, but nonetheless remarkably similar, that revealed the police to not be the guardians of ‘the rule of law’ as liberal common sense imagines them.

Some highlights:

On the 11th April 2020 in Glasgow, a woman with a joint condition who was carrying bags of shopping decided to sit down due to the pain in her legs. She was ordered to not sit down due to Covid restrictions. The woman explained that she had a joint condition. She was yelled at, threatened with a fine, interrogated over whether she herself was going to disinfect the bench, and ordered to leave. She was also followed by the police to ensure she was definitely walking home (Big Brother Watch, 2020a, p.32). On the 15th April 2020, another disabled woman sat down on a park bench due to pain. Police threatened her with a fine. The woman informed the police that she was disabled. She was told: “you’re not disabled” (ibid, p.32). The Coronavirus Act did not prohibit the act of sitting on a park bench. Nor did it demand that people should disinfect benches they sat on. It did not grant officers powers to classify who was and who was not disabled.

On the 10th April 2020, a woman was doing yoga in a park. She was moved on – the police informed her that she was “pretending to exercise”. A cyclist was informed that he had to go home as his cycling did not constitute exercise because he “wasn’t sweating”. A journalist who was walking in the park was told to go home because walking wasn’t exercise – only jogging and cycling were. (Big Brother Watch, 2020b, p.30). Derbyshire Police published drone footage of a couple walking their dog, and people exercising in the Peak District. The video contained the statement: “The Government advice is clear. You should only travel if it is essential. Travelling to remote areas of the Peak District for your exercise is not essential.” (Big Brother Watch, 2020a, pp.25-26). The Coronavirus Act did not define what constituted exercise. Nor did it prohibit driving to remote locations to exercise. The Derbyshire Police statement is particularly instructive due to its bluntness – they explicitly state they are implementing government advice, not law. Why were the police, consciously or unconsciously, implementing government guidance? What was going on?

In a previous blog post, I wrote about how the excesses of police discretion arise from the police’s obsession with order-maintenance. This partly explains what’s happening here. During a pandemic – a health-related state of emergency – certain clusters of actions can be viewed as disorderly, even if not legally restricted. The implementation of government guidance overlaps with the order-maintenance mandate. The centrality of order-maintenance can also be seen in instances of higher-ranking officers, who by dint of their position know what the law is, publicly declaring that they are going to start inspecting people’s shopping trolleys in supermarkets to see if they’re purchasing “essential” items, or patrolling “non-essential” super-market aisles to prevent people buying products from said shelves (Big Brother Watch, 2020a, pp.37-38). This is order-maintenance – its characteristic form is zealous and melodramatic. To qualify thism there is also evidence to suggest that much policing conducted by lower-ranking officers derived from sincere confusion about what the law even was – thus zealous errors were made due to genuine incomprehension of the law.

In my previous post, I noted two ways of analysing the intention of police officers who misapply the law: stupidity and lack of knowledge about the law vs knowing what the law states but cynically using it to achieve ‘order’. As before, I am going to sidestep the question of intent. What is interesting about these cases isn’t the intent of the officers, it is what they did: radically re-interpreted the law and/or outright invented it.

Policing and the ‘Separation of Powers’

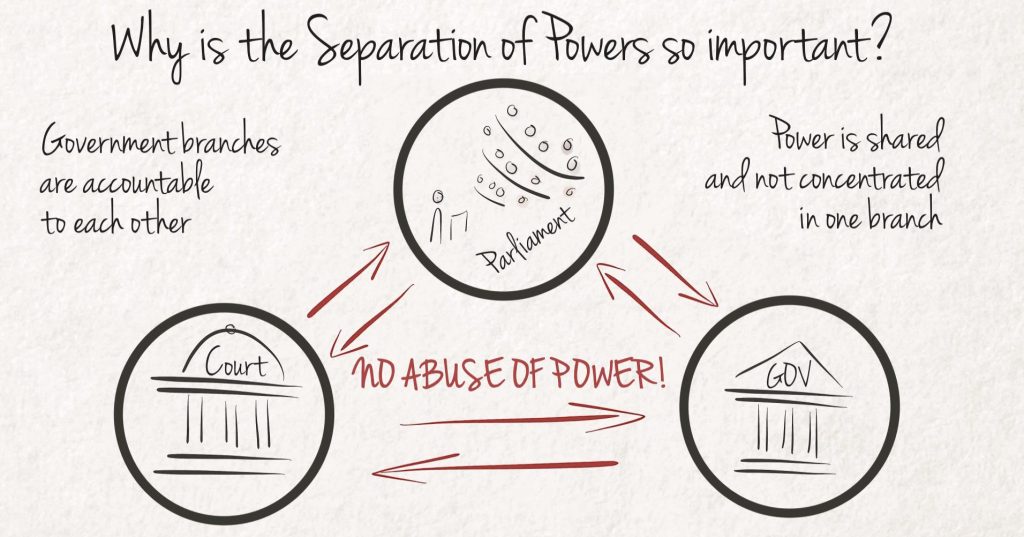

In a standard A-level politics class, you will be told that in a liberal democracy, you are free because the state is divided into three separate branches: the executive (i.e. the acting government); the legislature (i.e. elected politicians in parliament); the judiciary (i.e. judges who interpret the laws). The theory goes like this: states are parasitic institutions that inherently seek power, this means states always have the capacity to be tyrannical; to prevent tyranny, states must be divided up into differing components to ensure that any elected government always has its hands tied, the idea being that tyranny is stopped because governing is transformed into a logistical nightmare. This theory may prove useful to some extent – governments in liberal-democratic states cannot do everything they want because “the courts”, “lefty lawyers”, “rebel MPs” get in the way. However, when we analyse the police, the theory breaks down. Why?

Formally, the police are part of the executive wing – they fall under the purview of the Home Office. They are thus, officially, executive agents. This is not to say Yvette Cooper directly tells the police what to do in every scenario. The everyday operations of policing are not formally directed by the Home Office; the Home Office merely provides general policy, funding, strategy, etc. This qualification aside, the police are quite clearly part of the executive. But this is not all.

Police Studies scholars have noted that the police are also pseudo-judicial agents. When a police officer assesses a situation and fits a law onto it, he is interpreting the law. He is a streetcorner judge. Viewing him as a streetcorner judge becomes especially apt when we look at legal processes where the gap between the ‘crime’ and the punishment is fast-paced, such as in the issuing of Fixed Penalty Notices, i.e. fines. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the pseudo-judicial character of the police intensified simply due to the amount of Fixed Penalty Notices that could be handed out.

However, the analysis goes further. In the case of the Covid-19 pandemic, the police did not simply interpret the law in unusual or eccentric ways, they were also completely inventing what the law was. They simply made up legal infractions, coined new crimes (consciously or unconsciously) – and acted on these pronouncements, enshrining them with official action. We may ask ourselves the question what ‘the law’ is. Is ‘the law’ simply what is written on a piece of paper, or is it more complex, a contested series of processes that begins in parliament but does not stop there? One analysis, the liberal one, says that the law is what is formally written – what the police did wasn’t implementing the law at all. What they were doing was illegal. This is all well and good to some extent. At the technical level, yes, the question of the law – formally written – not fitting police action, arises. However, the police are the physical embodiment of ‘the law’. They fine, arrest, move on, harass, follow home, and yell at people – and most individuals do not formally challenge this in the courts. Police action has a finality to it. In other words, in practice, this is what ‘the law’ actually amounted to. You might say, “yes, but this action broke the rules as written”. This is true. But the crucial point is that the police still had the ability to invent the law they were implementing. They are pseudo-legislative agents.

This character becomes crystal clear in the recent cases of officers using terrorism legislation against individuals who are not in Palestine Action and not endorsing Palestine Action. They really do, quite simply, invent the law.

Policing straddles the executive, the legislature and the judiciary. It does so in contradictory ways (sometimes courts can overturn their decisions; sometimes the police do not invent the law, in other moments, like the pandemic, the pseudo-legislative component runs rampant). The police, as an institution, is extremely strange. It does not seem to be easily restrained by liberal constitutionalism. This is why liberals do not understand it. They start from the assumption that the police are simply executive agents. Their solution to policing is that the police should follow the rule of law. The police should simply be legal technicians with tasers – individuals that walk around, spotting crimes, and neutrally applying the law to all. But this is not what the police do, nor can it be, because policing is not and can never be meaningfully constrained by liberal constitutionalism. The police officer is a miniature-Leviathan.

References

Big Brother Watch (2020a) Emergency Powers and Civil Liberties Report [April 2020]. Available at: https://bigbrotherwatch.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Emergency-Powers-and-Civil-Liberties-Report-april-2020.pdf.

Big Brother Watch (2020b) Emergency Powers and Civil Liberties Report [May 2020]. Available at: https://bigbrotherwatch.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Emergency-Powers-and-Civil-Liberties-Report-May-2020-Final.pdf.

Leave a comment